Green gold rush: the ethical landscape of rare earth mining

Read time: 4 minutes

Read time: 4 minutes

Green technology depends on rare earth materials. Lithium is used in the batteries which power EVs, cobalt goes into the design of wind turbines, and nickel is a key component of solar panels. But sourcing these materials raises ethical concerns, including forced labour and so-called eco-colonialism.

Green tech leaders need to think critically about the design of their product and the origins of the materials that go into them. This means having a clear image of your product’s lifecycle and communicating this clearly to customers and shareholders.

The mining of rare earth metals (REMs) raises a variety of ethical questions: Firstly, there’s the labour being used to extract these metals. Secondly, the environmental impact of mining and, in some cases, over mining. And thirdly, the disposal of these REMs once the product they are a part of reaches end of life.

Digging into issues of labour, the mining of REMs has been closely linked to forced labour camps and slavery across the world, particularly in Africa, including South Africa, Namibia, Angola and Uganda, and China.

China’s ties to forced labour in the REM market is particularly concerning, since it holds the largest reserves of REMs globally, equating to roughly 44 million metric tons. While China has a plethora of compliant mines, it has also been associated with forced labour mines in the Uyghur Regions which are found in the North-West of the country. In these regions, China was outed for undergoing state-imposed forced labour camps targeting the Uyghur Muslim population. Since these mines were discovered, China has orchestrated a crackdown on their REM sector, closing illegal mines and strengthening human rights labour protections.

Similar problems have been found across several African countries where mining practices are sometimes incredibly dangerous and reliant upon very basic machinery. This is why traceability is essential. If your product uses REMs and you are concerned about the practices which went into mining them, you need to start by tracing their origin. If you are unable to identify from where the REMs originated, this should raise alarm bells for you and your business.

While both Africa and China, have ethical, compliant mining practices, there are other countries with an abundant supply of REMs and a much cleaner record when it comes to mining. Greenland has made headlines recently as the US made moves to control some of its resources. This is because the island boasts 1.5mn metric tonnes of REMs, much of which isn’t even mined.

However, the US’s advances on Greenland’s territory and attempted claims to its land and resources opens up a much broader issue: eco-colonialism. This is a practice where rich, powerful nations attempt to exploit the resources and labour of other countries under the illusion that it is being done to enable sustainable development. Some of the most resource rich countries and regions in the world are considered “developing nations,” making them immediate targets for developed nations with ambitious green policies, but a lack of resources to support them.

Next, there’s the issue of rare earth mining and its immediate environmental impacts.

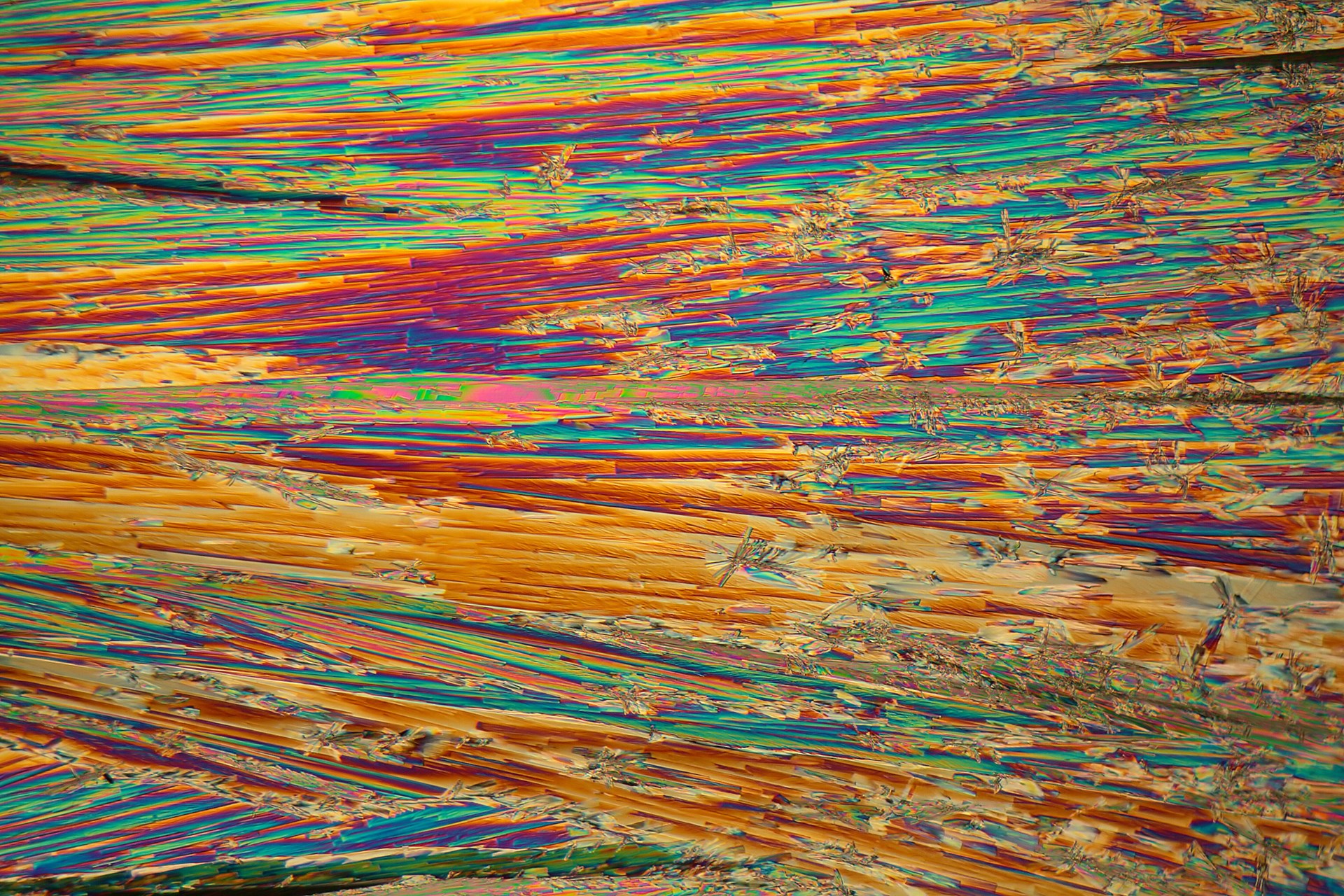

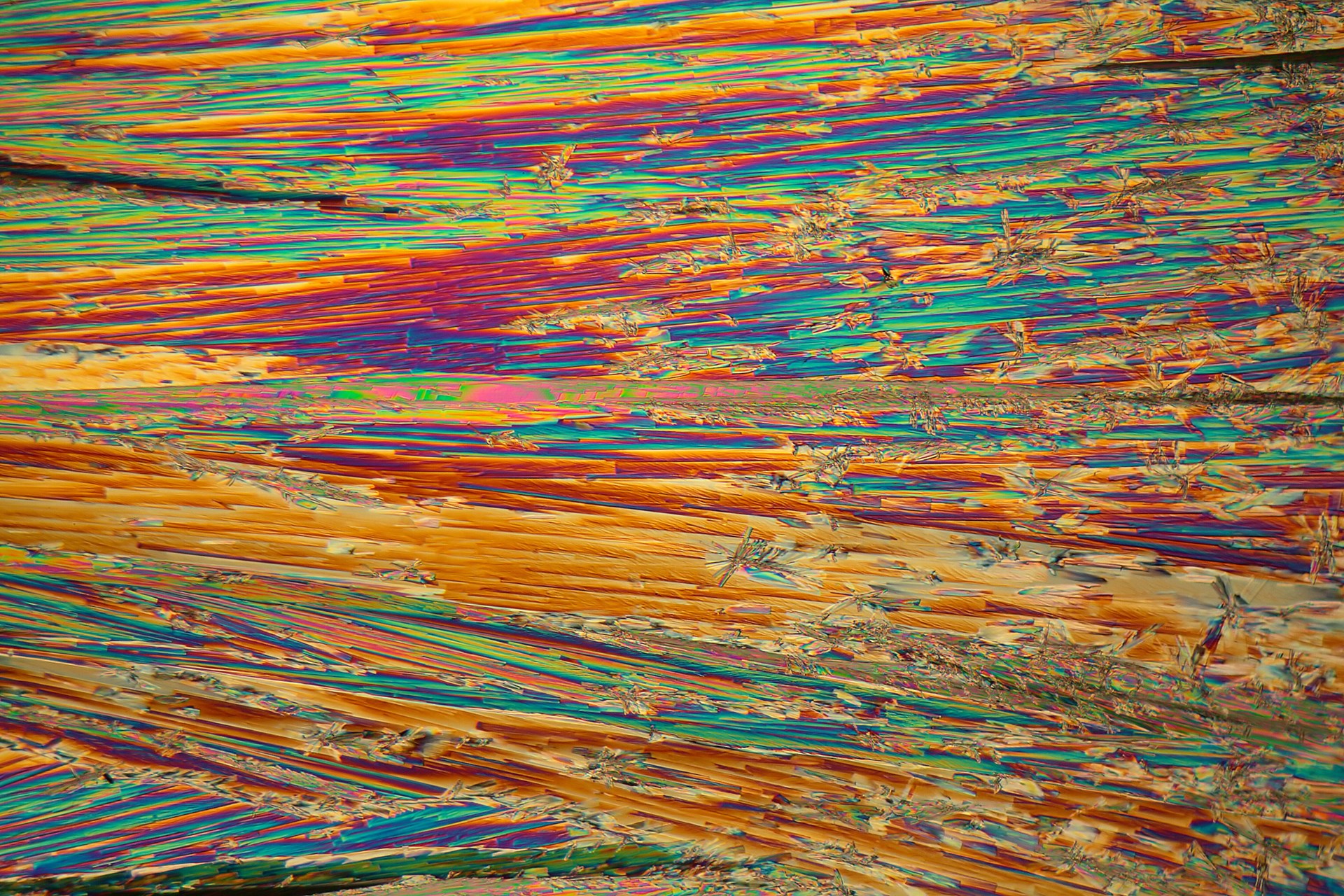

The mining of REMs releases toxic chemicals into the environment and disturbs large patches of land. Leaching ponds are a method of mining which involves removing topsoil and adding chemicals to separate metals, as the chemicals dissolve the rare earth materials, making them concentrated and refined. The issue is that leaching ponds cause leaks and chemical runoff into groundwater which are at risk of entering waterways.

Drilling creates similar issues to leaching ponds, using PVC pipes and rubber hoses to pump chemicals into the earth. According to EURARE, for every tonne of REMs produced, the process generates 13kg of dust, 9,600 – 12,000 cubic meters of waste gas, 75 cubic meters of wastewater, and a tonne of radioactive residue. Hardly the green process we envisage when discussing green technologies.

A solution to this impact is circularity. While the rare earth mining industry has a responsibility to innovate more efficient and environmentally conscious mining processes, organisations reliant upon REMs in the manufacture of their product should be placing more emphasis on circular economy solutions.

The UN Environment programme estimated that over 53 million tons of e-waste were generated in 2019 alone. Smartphones, laptops and tablets are rich with rare earth elements such as indium, tantalum, lithium, cobalt, copper, and much more. All of these REMs are valuable to the green technology supply chain.

Leaning into e-waste recycling solutions and partnering with accredited e-waste facilities who specialise in managing disposed electronics and extracting their materials is a fundamental approach to tendering the ethics of rare earth mining. Not only does it avoid the negative environmental impacts of mining new rare earth elements, but it also lessens the chances of generating more work for mines with unethical labour practices.

As rare earth metals become hot property globally, it’s essential that we avoid doing what humans do best, overexploiting a resource for quick financial gain. Ethics are closely linked to the environmental mission, so one cannot be achieved without significant effort being directed into the other.

Think circularity. Think supply chains. Think responsibly.

Share